There are many religious groups around the United States that practice shunning; they turn away from congregates who leave the group even those from their immediate families. Experts call shunning a form of psychological bullying.

Community Voices producer Brad Price learned about groups in the Miami Valley that practice shunning and has this story about a young man who was shunned – and how he survived.

A couple I recently met who I’ll call Sidney and Silvia invited me over to their house on a Saturday morning. After letting me inside, Sidney got busy making breakfast - bacon, Eggs, toast, and some weird corn dog shaped pancake-sausage combo I had never seen. The couple's happiness is magnetic, but achieving that happiness has been difficult for Sidney. A few years ago, almost every relationship with friends and family he has had since birth was taken from him.

Sidney grew up a member of a fundamentalist Christian sect in The Miami Valley. As a teenager, he began to recognize his moral and intellectual disagreements with his own faith tradition. His willingness to be vulnerably honest about his change in beliefs triggered a devastating disconnection from his friends and family.

"When you can't believe what they believe, and everybody tries to make it seem like you chose this path where you’re not going to believe anything, that’s enough of a difference between you and that person, and that’s enough of a difference for them not to speak to you or to want anything to do with you again and to consider you basically dead to them, to consider you dead to them. I mean, that’s how it feels," says Sidney.

I began talking to many people in the Dayton area who’ve had this experience. They say the silence of their family and former friends is deafening. Recognizing how devastating this type of rejection is, I wondered how common it was, but that’s part of what makes this behavior so insidious, it seems impossible to quantify it.

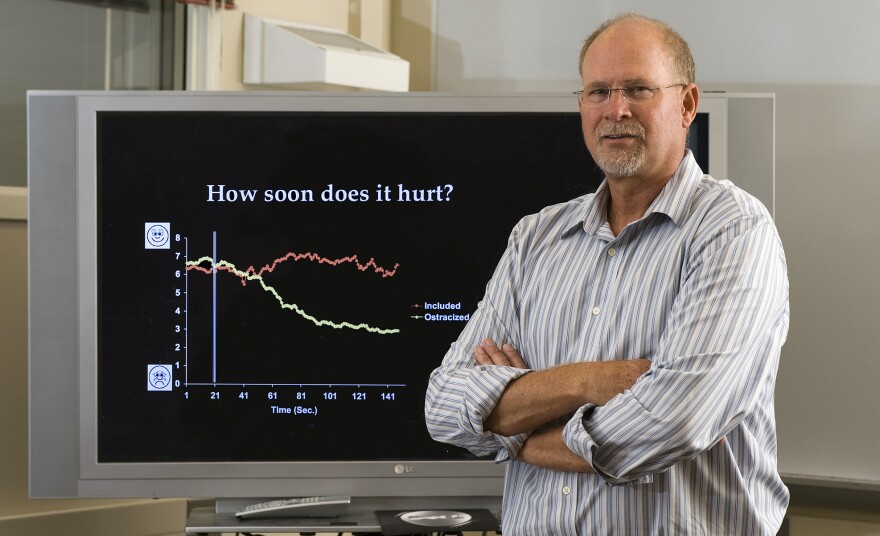

"It’s easy to find a bullying situation where someone is being hit or yelled at or made fun of," says Dr Kip Williams at Purdue University. He studies the psychological effects of ostracism. "But not being looked at, not being answered at, not being talked to is an absence of a behavior rather than a behavior so it’s harder to document and to prove and to prosecute and all sorts of things."

Dr Williams says that the psychological pain from ostracism produces the same patterns in the brain associated with physical pain and that it can be deadly. His research shows there is a high prevalence of suicidal tendencies among those who have been ostracized. I asked Sidney if he ever considered taking his life.

"You do think that there may be nothing else for you. If there's nothing else, all there is is this suffering, this miserable rejection."

"Yeah as far as being in a dark suicidal place, I spent years there. You do think that there may be nothing else for you. If there’s nothing else, all there is is this suffering, this miserable rejection. Yeah, you do want to kill yourself.

Despite having been in this dark place, Sidney seemed happy the morning I met him and Sylvia. He says things started to turn around when he met her.

"We just right away clicked really well," says Sylvia. "And so like, right away we started hanging out a lot and we got along really well. We both really made each other laugh, but yeah, just generally in life overall he’s just more excited about things and has a really good group of friends now."

"I don’t have any of the real significant problems that I had earlier in life," says Sidney. "And I also don’t have this humongous weight of depression that I had since early teens of never being able to be this thing that I was expected to be. I’m still not that thing, but the difference is now I’m okay with it."

I asked Sidney what he would tell his former friends and family about his life if they would talk to him.

"I would probably…I would tell them that I was happy…that right now, in my life, I’m happy but they’re still missing."

To find out more information about the psychological effects of ostracism, visit Dr Williams’ website at williams.socialpsychology.org