WYSO holds a rich digital archive from the Civil Rights era. As we approach the 50th anniversary of the Civil Rights Act in 2014, we’re partnering with community organizations to augment it with the stories of local residents who lived through this transformational period in our history.

Community Voices producer Jocelyn Robinson used the historical audio to inspire childhood recollections of the day when the streets of Yellow Springs looked more like the streets of Birmingham, Alabama.

In September 1963, over four hundred people marched through the village to mourn four little girls killed in a southern church bombing, and to strengthen their resolve to integrate a downtown barbershop.

In the weeks after the march, local protests were escalating in front of Lou Gegner’s barbershop. On March 14, 1964, villagers and Antioch students were joined by students from nearby Central State and Wilberforce colleges. Hundreds of people lined the streets of Yellow Springs to bear witness to what was about to happen.

Sterling Wright was a young teenager.

“I remember getting up in the morning and my parents telling me don’t go downtown because there’s going to be problems,” Wright says, “But I was 13 at the time, and myself and a lot of our friends were gonna go down there anyway, out of curiosity.”

Bomani Moyenda was only ten years old.

Moyenda says, “I remember my mother taking my sister and I down there that day, and standing and watching, and the students linked arm in arm you know, across the street. I wasn’t exactly sure what was going on but I knew it was about this white man who refused to serve Black customers.”

“So as we approached the town,” Wright remembers, “Me and a few of my friends we started talking and we were very well aware of what was going on in the United States, the demonstrations, freedom riders, the lynchings. We were very, very well aware, and we were very shocked that that could happen here in our hometown.”

“To see that many people, like occupying downtown and the tension that was in the air, you know, to sense that, and to hear the singing and the shouts of the protesters you know, it was really intense,” Moyenda says.

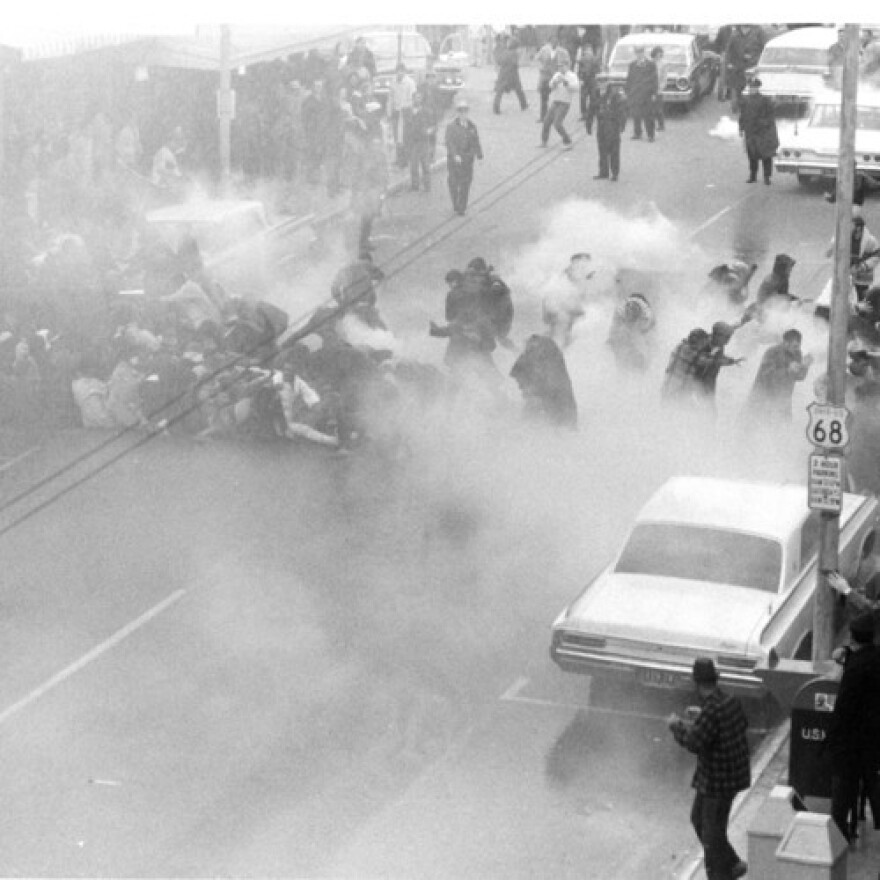

It was so intense that officers in riot gear used nightsticks and fire hoses to break up the demonstrators. Villagers watching from the sidewalks fled, blinded and choking as tear gas billowed through the crowd. Abandoning nonviolence, some protestors actively resisted arrest, and over a hundred people were hauled off to jail. Years of insistent but peaceful protests ended up in a race riot that was carried on the national evening news. The barber closed the shop that day, never to reopen, never to integrate.

But the Movement marched on. That summer, busloads of volunteers from all over the country headed for Mississippi to open Freedom Schools and register Black voters. Congress passed the Civil Rights Bill in June, making integration the law of the land. The following spring, Martin Luther King, the drum major of the Movement, gave the commencement address at Antioch College.

Now, nearly 50 years into the new age, Yellow Springs is considered a liberal haven in conservative Southwest Ohio. Yet many current residents have no knowledge of its Civil Rights legacy, no memory of its role in our nation’s struggle for equality.

Robin Jordan-Henry, a member of The 365 Project, one of WYSO’s partners in collecting oral histories to enhance the historical recordings, explains the importance of gathering and preserving stories like those of Sterling Wright and Bomani Moyenda.

“We need their stories because we need to understand this village,” Jordan-Henry says, “We need to understand what people have gone through in order to make this village what it is now, or even keep working to make this village what it ought to be, what it purports itself to be. And also just for a more realistic view of who this village is.”

Eventually, WYSO’s archives and the oral histories will be available to researchers and scholars. But memories of pivotal events in our history belong to all of us. It’s our shared story, whether you lived through it or not. And it shapes the character of our community, past, present, and future.

“People should kinda use that incident as an anchor, and really focus on the values that were present during that time, the values of social and racial justice, and really use that history and energy to focus on doing some anti-racism work on a personal level,” Moyenda says.

Wright agrees. “I think going forward, if you forget the past, you have no future. I think Yellow Springs is a sleeping giant. I do believe that the new community that moved here because of the good things that they wanted to see, that if we can charge them socially, that we can make some major changes here.”