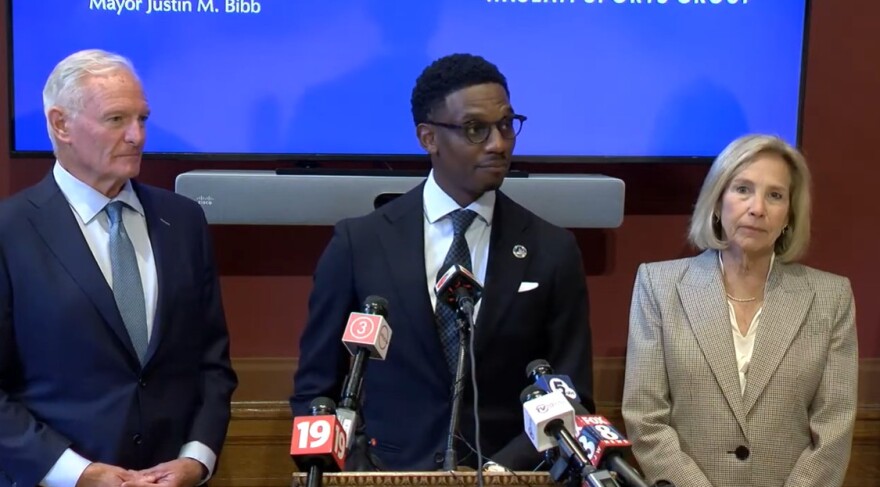

As Cleveland Mayor Justin Bibb and the Haslam Sports Group work to firm up a $100 million deal to drop lawsuits related to the team's move out of the city, several Cleveland City Council members, who will have to approve certain elements of that deal, say they're not yet sold.

In a more than three-hour hearing Monday, Bibb's administration came before members of council to discuss negotiations with the Haslams ahead of a Nov. 24 deadline for council approval.

That tentative agreement includes a $25 million upfront payment to the city by the end of the year, demolition of the downtown stadium and tens of millions toward community projects after the team's lease ends after the 2028 season. In exchange, the city would drop all related lawsuits regarding the Haslams' $2.4 billion enclosed stadium complex in Brook Park.

After Bibb announced the deal last Monday, some members of council expressed outrage, with Brian Kazy saying the mayor had "lied with the dogs" and now has "fleas".

That frustration continued in Monday's hearing, as council members criticized the mayor for letting the team go and not getting more to show for it.

"I'm trying to justify this with my own brain," said Council member Mike Polensek. "At the end of this deal we wind up with nothing."

Bibb defended the decision as the best he could do for taxpayers.

"In no world would I ever try to leave money on the table," Bibb said. "I'm willing to take the political hit. Some will say, 'Mayor Bibb sold us out.' Some will say, 'Mayor Bibb should have got us $300 million or $700 million.' Those are great what-ifs. If I saw a path to get $700 million, I would have fought like hell to get it."

Bibb described unexpected obstacles, such as the state Legislature approving $600 million in public money toward the Brook Park stadium and a rewrite of the Art Modell law intended to block teams playing in taxpayer-funded facilities from leaving.

"You told me specifically, 'We need to get a lot of money from them, protect the taxpayers and not be left empty handed,'" Bibb told members of council. "And I believe this settlement does that."

Bibb said he could not put his faith in the courts and the Republican-controlled Statehouse for a favorable outcome for Clevelanders.

Even if the lawsuits had ruled in favor of the city, Law Director Mark Griffin said there was nothing stopping the Browns from leaving when their lease expired at the end of 2028.

The alternative, he said, was nothing for Cleveland.

"The Browns have made it very clear they were going to Brook Park," said Jessica Trivisonno, the city's senior advisor for major projects. "There was a lot of ways we tried to stand in the way of that... but there was no way for us to force them to stay in Cleveland beyond 2029."

The administration cited past attempts to keep the Browns in the city-owned lakefront stadium, including a half-billion dollar incentive package with no bites.

Council members worried about long-term economic impact caused by the team's departure. The city previously projected a $30 million annual loss to its economy if the Browns left.

But the administration said those impacts were coming regardless of the settlement, and the money from this deal will help mitigate those economic headwinds. Part of the settlement includes a massive influx of cash toward the sweeping downtown lakefront plan.

Aside from economic impact, some discussed shattered nostalgia; gone are the days of watching a game at the downtown stadium or in front of the TV set with your dad in support of the hometown team, Kazy said.

Kazy said he plans to introduce a resolution calling on Jimmy Haslam to drop "Cleveland" from the name, instead pushing for the "Brook Park Browns."

"I kind of look at this like dating a girl that doesn't want to be with you anymore," Kazy said. "Common sense tells you, let her go. But your heart tells you, right, that team belongs in the City of Cleveland."

Others expressed concern about a typical Cleveland resident's ability to even get in the door after Haslam told the Associated Press the average ticket at the new stadium will cost more than $200.

"I think that the biggest loser in this whole thing is the working class in Cleveland, because I don't think blue collar people will ever go to another Browns game again," said Council member Kris Harsh.

Despite a tense hearing at times, Bibb will need council's approval to finalize the deal. Though Cleveland's law director has discretion over the status of city lawsuits, council is responsible for approving key elements of the settlement, including accepting donations and approving demolition.

That term sheet is coming before council for approval by Nov. 24.

If council fails to act before then, the administration said it could delay the $25 million upfront payment.

In the meantime, the three lawsuits between the city and team remain active: A city suit invoking the Art Modell law, a federal suit from the Haslams calling that law unconstitutional, and a city suit alleging the team's violation of their lease.

Another taxpayer suit, filed by former Cleveland Mayor Dennis Kucinich, takes aim at both the city and the Browns.