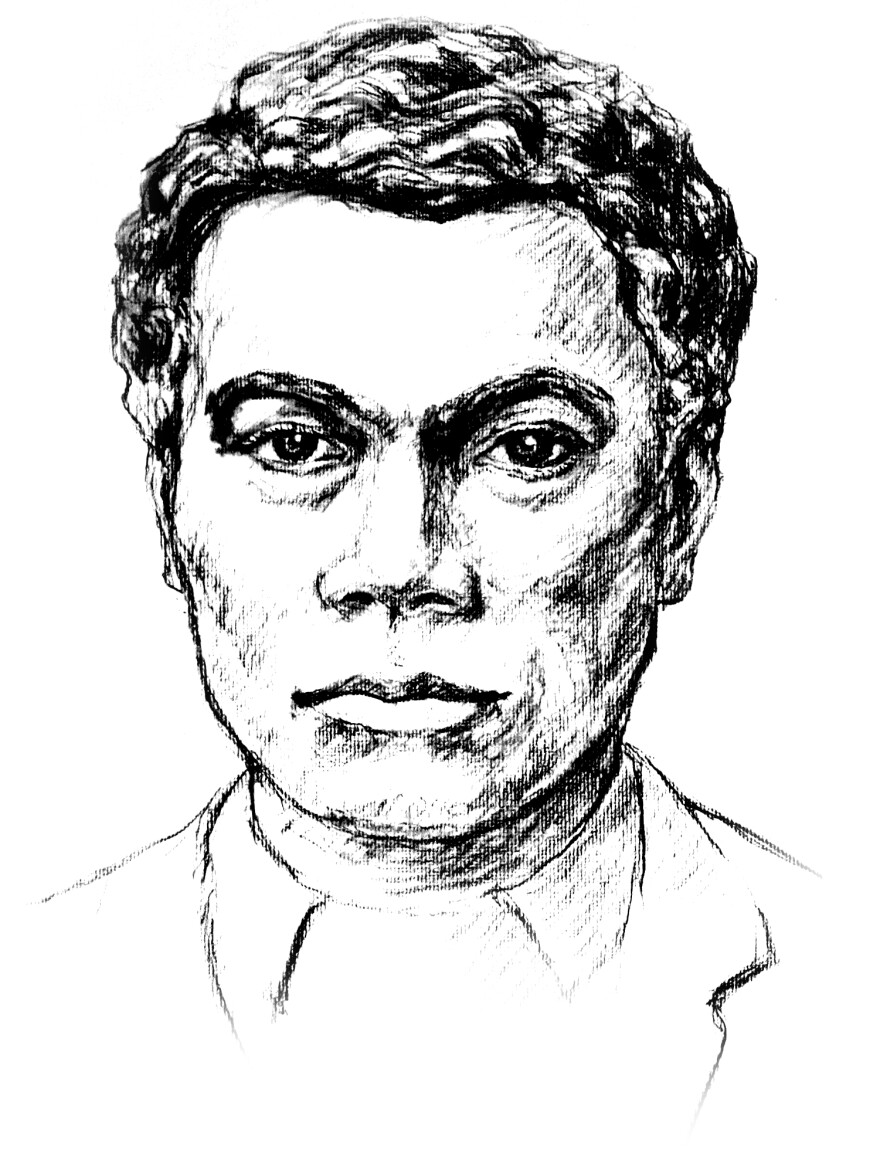

As of a few weeks ago, when you visit Yellow Springs, you're going to see something new: a life size bronze statue of Wheeling Gaunt. He stands at the entrance of town from Route 68 with one hand welcoming visitors and the other firmly placed on his hip. Many people may know of this once enslaved man’s gift of yearly flour and sugar for widows. Yet there’s much more.

Wheeling Gaunt purchased his freedom in Carrolton, Kentucky after his slaveowner father died. His father had priced him at $600. Relatives demanded $900. Years later, Wheeling also purchased his wife’s freedom and likely a son’s. He could only work as a laborer, but he saved money so well over so many years, he started buying property.

When formerly enslaved people could own property, they could better control their destiny, says Kevin McGruder, professor of African American history at Antioch College. “I suspect anybody born enslaved watching what slaveowners did and the power that land gave them understood very early on that land ownership was important in America."

Brenda Hubbard, author of Legacy of Grace: Musings on the Life and Times of Wheeling Gaunt believes Gaunt had a plan for his properties in Carollton, Kentucky. “When he lived in Carrollton,” says Hubbard, “ he purchased property right next to or part of the downtown commercial area. So he was a very good strategic thinker about what it would mean to have a property and where it would be best located.“

The Civil War and the precariousness of Kentucky as a possible slave state during the war forced Gaunt and his wife family to flee Kentucky. Historians say he came to Yellow Springs because he sought the home of Reverend Daniel Payne of Wilberforce University and the newly formed African Methodist Episcopal Church. Gaunt hauled goods by day and kept up his real estate strategy, eventually owning a whole block of homes next to the commercial district in Yellow Springs. To do this, he conducted business with white men in town.

Kevin McGruder believes Gaunt’s business dealings tells us something about the history of Yellow Springs as a more welcoming community for African Americans than most neighboring towns.

“Because there’s some communities not that far from here where he knew, I bet, that there was no point in trying to do anything there, that he wouldn’t have been taken seriously or he might have been met with violence.”

Census records show that Gaunt often rented to black families. His properties helped provide a safe haven and supported a network in the AME church and Black community groups. Brenda Hubbard tells of one family that Gaunt helped, among many. “So you find documents where he purchased real estate and then sold it to a mixed race family, the Mingos, for a dollar,” says Hubbard. “ And then the Mingos started a business on Corry Street. By helping them get a foothold, then they develop a business.”

On his death, Gaunt willed his properties to Wilberforce University and $5,000 to the AME church as well as gifted the nine acres of farmland to the village to finance the widow’s fund for yearly flour donations. Gaunt could do so much for others because he was part of a larger Black network of families and businesses.

“When we move into the 20th century and we see more visible Black leadership,” Kevin McGruder points out, “some of them are the children and grandchildren of people of Gaunt’s generation who remained here. I think it’s kind of the core of community where there’s a care for each other and the institutions that they form, the relationships that they have.”

Cheryl Durgans is the project manager for the Wheeling Gaunt sculpture. She grew up in the Black community of Yellow Springs and remembers that spirit of generosity that she believes is Gaunt’s legacy to the town. “My father around the holidays gave money to widows in the church and my family,” Durgans recalls. “We were considered the Hotel Durgans, you know. We had people at any point in time staying here who may have, they just had some challenges and needed a place to land for a month or two.”

Durgans looks back with pride at Wheeling Gaunt’s generation and sees a model for the future of Yellow Springs in the motto said by Gaunt: “Not what we have, but we share.” Durgans reflects on Gaunt’s generosity in the face of such adversity. “ And so we have an example of somebody who owned property but didn’t exploit it, but didn’t bundle it, you know, for his own personal gain, and at the same time was considered property. And I believe for the African American community, he offered an example that there was hope, you know? It was like this is something that we can do as a community.”

Support for Culture Couch comes from WYSO Leaders Frank Scenna and Heather Bailey, who are proud to support storytelling that sparks curiosity, highlights creativity and builds community.

Culture Couch is created at the Eichelberger Center for Community Voices at WYSO.