At the Aviation Trail Parachute Museum in Dayton, a timeline wraps around the room, detailing the invention of the life-saving contraption.

It begins centuries ago, circa 1485.

“What we do here is start with Leonardo da Vinci's ideas and concepts,” said Randy Zuercher, the museum’s curator.

Da Vinci’s original triangular parachute design actually works. But over time, it evolved from stiff wooden contraptions with heavy wooden frames to silk canopies that unfold from backpacks.

Those early silky models connected to aircrafts via lanyards. A person would jump out with the lanyard still attached and gravity would pull the cord, releasing the chute.

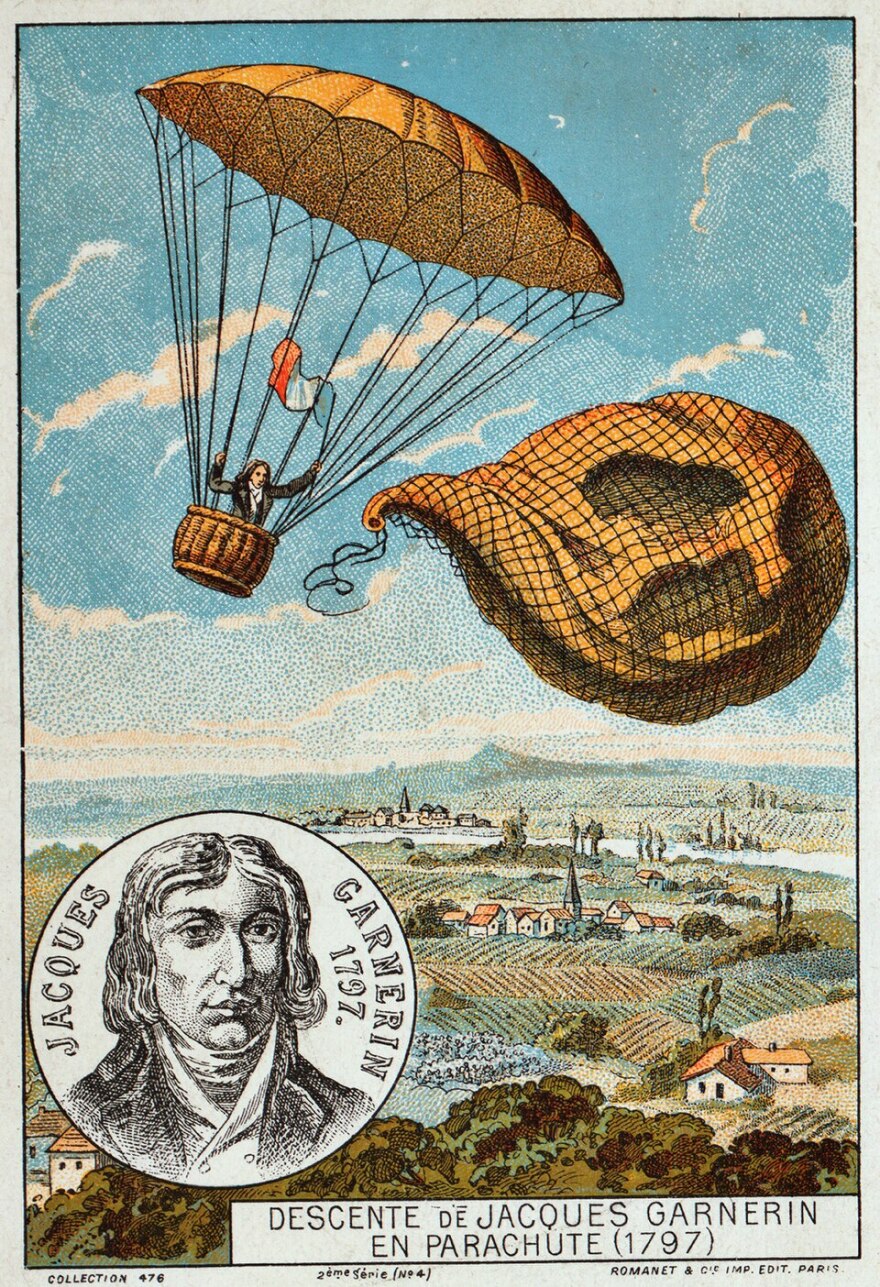

They worked fine for descending from a hovering hot air balloon, Zuercher said. But they were less effective for pilots on planes spinning out of control in the middle of World War I.

“Think about it,” Zuercher said. “Do you want to be attached to a failing aircraft? Not a good idea.”

The U.S. military needed a better solution: The Allied Forces were losing pilots by the thousands.

Enter Dayton, Ohio.

The role of McCook Field

Before the Air Force, the Army Air Service did its research and development at McCook Field, in southwest Ohio.

“So McCook Field developed all kinds of very special instrumentation,” Zuercher said. “The very first radio navigation for aircraft was developed here. The first helicopter was developed here.”

At the end of WWI, circus trapeze artist turned aviator James Floyd Smith was leading a team at McCook Field to develop a more effective parachute.

Like earlier models, he designed a chute that unfolded from a backpack. But unlike earlier models, the parachute didn’t need to be attached to an aircraft to deploy.

“So this new development allowed the pilot to get away from the aircraft and manually pull the ripcord,” Zuercher said. “It was so much safer.”

But at the time, there were skeptics. They questioned whether a person in free fall would lose consciousness or be too disoriented to pull a ripcord.

So on April 28, 1919, Smith did a test run.

He flew a plane at an altitude of 1,500 feet over McCook Field. Stuntman Leslie Irvin jumped. He pulled the ripcord. The parachute opened. And he survived, albeit with a broken ankle.

The free-fall parachute for emergencies

Three years later, Lt. Harold Harris was in mock combat over McCook Field when his plane started to fall apart. He’s believed to be one of — if not the first — airmen to use the free fall parachute in an emergency.

He lived to write about the experience and recounted pulling on the ripcord over and over again as he fell.

“My body was spinning, falling head first toward the ground,” he wrote. “I then discovered I had been pulling on a leg strap fitting on the chute's harness. I quickly found the correct ring and pulled. The parachute opened almost immediately, with a considerable jerk snapping my body around so that my feet were finally facing the ground.”

He landed with only minor bruises to show for the fall.

Later, the U.S. ordered all military pilots to fly with free-fall parachutes.

Today, the lifesaving devices are made with nylon instead of silk. There have been some technical changes to the device over the decades, Zuercher said.

“But it has not really changed radically since then,” he said. “The concept is pretty much the same.”

Zuercher would know. He’s jumped out of a plane nearly 500 times — with no injuries to show for it.