Ohio is filled with public art.

In Columbus, bronze deer statues rest on their elbows, overlooking the Scioto River. In Cleveland, a giant FREE stamp sits on its side near the waterfront of Lake Erie. In Dayton, a tribute to the Wright brothers abstractly recreates their first 12-second flight.

But Ironton, in southern Ohio, has a canvas unique to river towns.

The floodwalls built around the city protect it from the rushing Ohio River, but they also are the backdrop for the city’s history.

Sam Heighton, the executive director of Ironton Alive, a community revitalization organization, points to a black engine painted onto the concrete wall. Steam billows from its two-dimensional smokestack.

“That railroad was built by Henry Ford around 1910,” Heighton said. “He would haul steel from the Ironton steel plant that we had all the way to Detroit on this railroad.”

To this day, Heighton says the train station is the oldest building in town.

That’s why he believes the railroad deserves a prominent spot on the floodwall.

For years, its stone face has proudly displayed images of local people and places in a tapestry of the city’s history. But these days, many murals are sun-faded and peeling.

So Ironton Alive plans to repaint several this summer, hoping that preserving the city’s history will benefit the city’s future.

The story of Ironton’s floodwall

In 1937, the Ohio River rose so high it spilled into the streets of Ironton.

“All this area right here was underwater,” Heighton said, gesturing to a parking lot beside the floodwalls. “[The water] came up to the roof on that building there.”

Homes and businesses throughout the area were damaged and destroyed.

The next year, the city started building a towering wall so that high water could never threaten it again.

Up until that point, Ironton was flourishing — full of people, industry and even winning sports teams.

But in the decades following the flood, industries started closing and people rapidly moved out of town, leaving behind empty storefront windows and a concrete wall blocking the view of the river.

In an effort to beautify the place and preserve its history, a local group organized to cover the floodwall in murals in the ‘90s.

Beside the painting of the train engine is a portrait of Nannie Kelly Wright. Legend has it, she was the only female ironmaster in the United States and one of the richest women in the world.

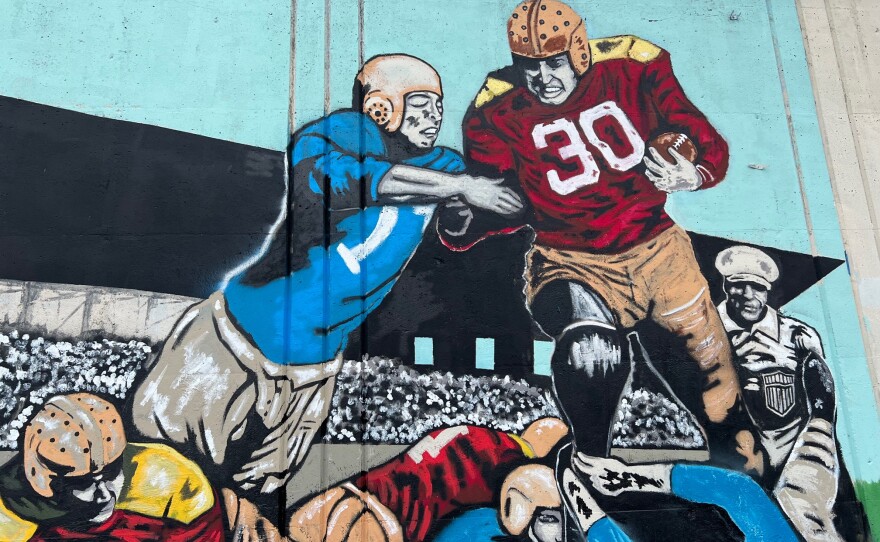

There’s a tribute to local veteran William Lambert, the second-ranking American ace of World War I, a depiction of Ironton’s once-professional football team, an illustrated steamboat, and a painting of the Waterloo Wonders.

The high school basketball team won back-to-back state championships during the Great Depression. Heighton says they didn’t have a basketball so they had to improvise.

“They made the ball out of rags,” Heighton explained. “They couldn't dribble it. So they just passed it around real fast and got really good at making shots.”

Heighton says stories like these helped shape Ironton into what it is today.

“People die and people move on,” he said, “and when you're young they don't mean anything to you. But eventually you ask somebody what they're all about.”

Although he was too young to remember the floodwalls going up, Heighton is old enough to personally know some of the people featured on them.

That WWI ace wasn’t the friendliest neighbor, he remembers from when he was a kid.

“We didn't have television or cell phones, so we played outside and ran through people's backyards,” he said. “But we didn't run through his backyard because we knew he'd jump on us.”

But with the paint peeling and Heighton’s generation getting older, he worries stories like these could be forgotten.

The purpose of floodwall art

This summer, Ironton Alive plans to repaint some of the historic floodwall murals. The group is also organizing farmers markets and summer concerts and building pickleball courts as part of a larger effort to stimulate the local economy.

As the neighboring city of Portsmouth knows, illustrated floodwalls can play a role in that.

“We have visitors that come from overseas and have come to Portsmouth to see the murals,” said Donna Arnett, who works with the Portsmouth Area Chamber of Commerce and Portsmouth Murals, Inc.

Those tourists are a boon to local businesses, she said. But the murals aren’t just for out–of-towners.

“It adds community pride because it shows the community what we have had, what we've done, where we've come from.”

These days, floodwalls are the last defense among many disaster prevention strategies: better river management and dams also help control water levels. The majority of the time, they stand dry, serving another purpose: a testament to the city’s past and the passage of time.