Not long ago, turning an idea into a recorded song meant booking studio time, teaming up with skilled musicians and spending days, weeks or months shaping a sound.

Now it can take less than a minute.

Artificial intelligence platforms like Suno allow users to type in lyrics and describe a genre, then generate a finished recording almost instantly.

The tools are spreading quickly, raising big questions across the music world about creativity, copyright and other complexities.

In Northeast Ohio, artists are already navigating this new reality.

For some, AI is a powerful tool for experimentation and efficiency.

Others, however, feel it’s an unsettling shift that threatens livelihoods, originality and the humanity that makes art authentic.

Cleveland musician Michael McFarland, frontman of the indie rock band Messmaker, said the technology seemed to appear almost overnight.

“It was quietly building, and then it just exploded as this is something that we have to contend with because it's here now,” McFarland said.

Regardless of the legality, morality and ethics, he said it’s something musicians have to contend with. AI tools have already become commonplace in songwriting circles he works with in Nashville.

He said he sometimes uses Suno experimentally, describing it as a way to test how a song might sound in different genres.

“But the only way that we're going to get anywhere with this is if there's an actual human behind it,” he said.

A changing industry

Before tools like Suno, which offers a free version that allows any individual to create a full-length song in seconds, the typical approach to crafting music involved investing a significant amount of time and money.

“You spend between $400 and $800 to pay someone at a studio to play the guitars, to record the vocals, to program the drums, to do the whole arrangement,” McFarland said.

He was earning an income this way as a studio musician, but in the last six months he said he hasn’t had a single project come his way.

“It is absolutely affecting the bottom line of working producers, demo vocalists, all of the people that sort of supported the songwriting industry for the people that aren't artists and aren't vocalists and aren't producers,” he said.

Publishers, he adds, are cautious about AI-assisted material.

“We do a lot of pitching to publishers, and publishers are incredibly wary about anything that has a whiff of AI to it. Because they don't know the creative chain of custody that went into creating this piece,” he said.

In the music industry at large, publishers are responsible for licensing songs and collecting royalties for composers.

McFarland said musicians used to play rough demo tapes for publishers that featured original songs performed on a guitar or piano and vocals.

That begs the question: Can a musician pitch an AI song idea to a publisher?

“Or does it need to be an actual demo, or even just a work tape?” McFarland said. “There are some publishers that are like, ‘We want to go back to that, because we want to know that this was written by humans.’”

He said in his years as an audio engineer, he worked hard to smooth the “rough edges” of every song so it sounded crisp and clear.

Now he anticipates a trend where artists may want less of a polish to differentiate their music from AI.

“I think we're gonna start seeing a transition to leave the rough edge in there,” McFarland said.

Using AI as a tool

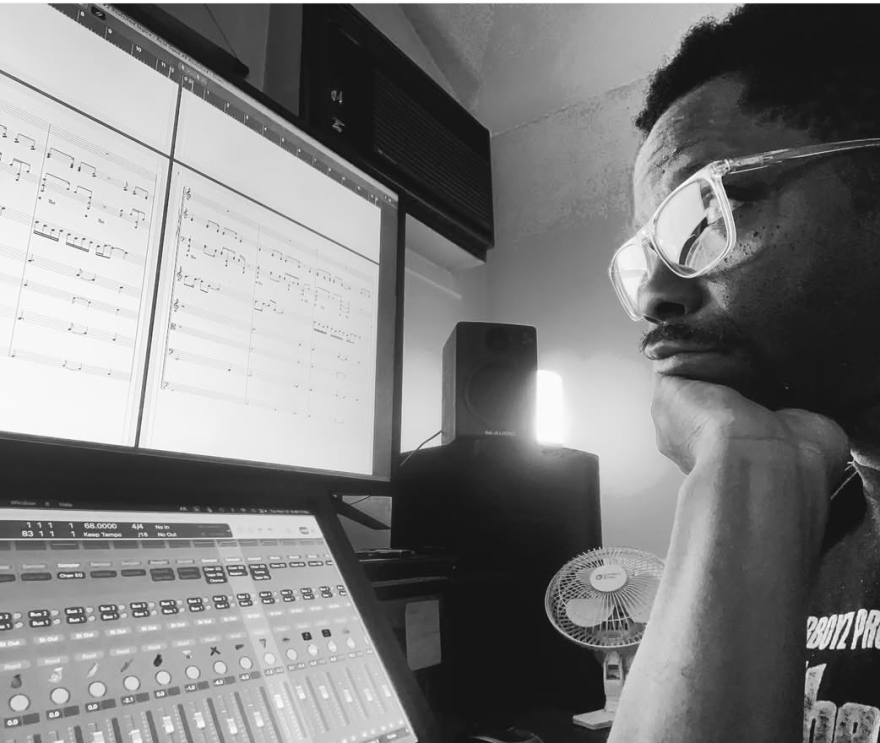

For Akron composer Eriq Troi, AI tools have become part of the creative process, particularly when developing demos or experimenting with arrangements.

“I'll send them a demo,” Troi said. “‘I like it, but can you speed it up?’ Sure. 'Can you make it sound real happy?' OK, another prompt. And that's how you use it.”

He said it makes his workload a lot faster and easier.

Troi also uses AI to help people who have musical ideas but don’t play instruments themselves.

One example was a piece written for his cousin, Chrishonna Greene, a therapist in Virginia who wanted a theme song for her podcast.

“I could hear it in my head, but I couldn't play it,” Greene said. “So that's what led me to Suno.”

Greene carefully described to the AI song generator what she wanted in a series of prompts.

“‘The R&B, jazz, blues, vocal, gospel and then make the run sound like this, and then add in background vocals,’” she said. “I just kept adding different things to the prompt. I ended up with three options that I could potentially go with.”

The speed of the process surprised her.

“It came together in like less than like a minute. It was mind-blowing to me,” she said. “It was also rewarding to hear something that matched what was like living inside of my mind.”

But there were limitations.

Songs created under Suno’s free plan aren’t owned by the user, so Greene asked Troi to recreate the piece with live instruments.

“And then he sent it back … and I was, like, in love,” Greene said. “And then I got even more sad, because it's like even if you've created the song with your own version, does it still mean that it belongs to Suno? He said, ‘I believe technically so.’”

Greene said the terms of AI platforms are something users need to understand.

“So, essentially, I'm going to pay for the song forever, because I use them as my collaborator and my producer,” she said. “What happens in 10 years when it's like, ‘You owe me $500 per year?’ So the rules are what you need to pay attention to.”

Legal questions

The legal landscape surrounding AI-generated music is still evolving.

Last month, Bandcamp, the popular online platform widely used by independent artists to sell music directly to fans, announced it would not allow AI-generated music on its site.

Los Angeles-based musicologist Judith Finell said U.S. copyright law currently protects works created by humans, leaving machine-generated music in uncertain territory.

“Say if you hear a guitar line and it was machine-created and you say, ‘Well, he copied yours or theirs.' There's a whole issue about whether or not that machine-created music could even own anything,” Finell said.

Finnell said she believes the courts will ultimately shape how the industry adapts.

“I think what will happen is that lawsuits will force it to the table,” she said. “There’s kind of like an arms race.”

That arms race, she explained, involves two sides: Tech companies that evolve by learning from pre-existing works and industries designed to protect artists and their original work.

“Artists who have given their, you know, so to speak, blood, sweat and tears to write their music or their symphony or whatever they're written, and then suddenly it's just taken without any permission,” she said.

Searching for the human sound

Beyond legal and financial concerns, some musicians worry about what AI could mean for originality.

Cleveland musician Bethany Joy said listeners may begin craving that sense of presence.

“Maybe the masses will go in the other direction, but I think a lot of people are gonna be missing and craving the humanness,” she said. “Like you listen to old recordings, you listen (to) Ray Charles, Nina Simone - God I've been listening to her records nonstop. You feel like you're in the room with her.”

She’s become more enchanted with the human side of making music.

“I want to hear the room. I want to hear the mistakes. I want that weird gurgle in your voice. I want somebody’s cough. I want the chair squeak,” she said.

Even artists who are cautious about AI acknowledge it isn’t going away.

Troi said he sees parallels with earlier technological shifts in music.

“It's technology, and technology, it jumps every two to three months. There's something new in technology, even with music equipment. I don't see it being any different,” Troi said.

When the synthesizer was introduced into mainstream music and artists like Stevie Wonder and Herbie Hancock began experimenting with the electronic instrument, people worried it would destroy their music’s authenticity and soul, Troi said.

“Then come along Devo, and then it's like, ‘Oh my God, they're gonna kill rock music.’ Then there's drum machines … and it's just this ongoing thing,” Troi said.

And for McFarland of Messmaker, one thing remains certain: The experience of live music still holds something that machines can’t replicate.

“At our core level, we are built and evolved to exist in community,” McFarland said. “I think that we might see a real Renaissance, like, ‘Let's go see the live music because everything else is fake.’”