As the United States coronavirus outbreak escalates, Ohio hospitals are taking new precautions to protect frontline health workers from unnecessary exposure to the highly infectious virus.

Doctors, nurses and other medical personnel are at especially high-risk of becoming sick with COVID-19. As the state prepares for a surge in cases, we hear from a longtime physician at the center of the crisis.

Dr. Hemant Shah heads up Kettering Hospital’s COVID-19 Critical Response Team, along with the COVID-19 Critical Response Teams at Troy Medical Center and Sycamore Medical Center. Shah tells WYSOs Jess Mador that while a good number of COVID-19 patients fully recover, even after being on ventilators, many others who contract the disease do not, and the unprecedented challenges involved in treating these critically ill patients are changing routine practices for the health workers who care for COVID-19 patients in the ICU.

What follows is a transcript of their conversation, edited for length and clarity.

SHAH: It changes completely how we practice just because of the tremendous infectivity and the very high mortality of patients getting very sick, patients dying. This is the first time that we have to now think about our safety first, putting that before the safety of the patient. And it's a very selfish thought. But if we don't do that, I will not be able to care for somebody else.

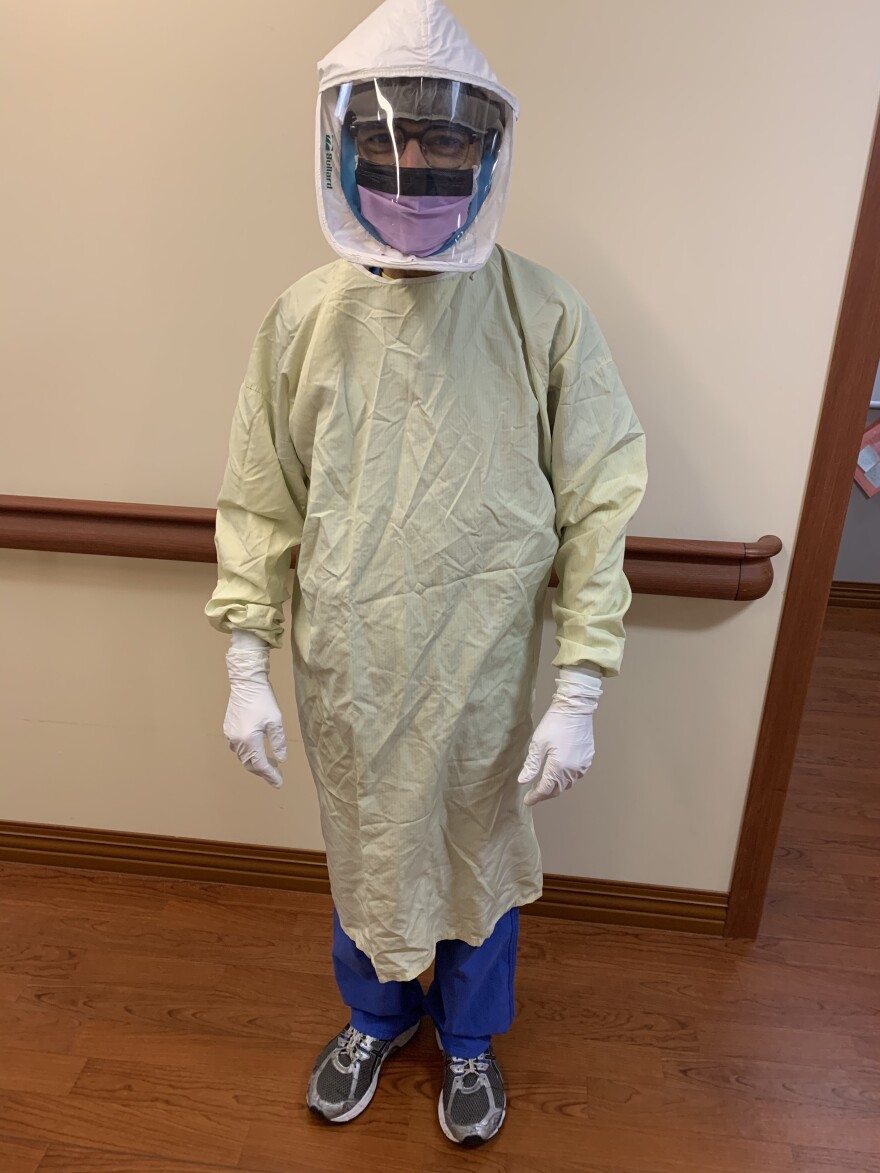

SHAH: When critical care patients deteriorate, it is the normal tendency of all these people in the critical care team to go in, check on them, come out. We can't do this anymore. First, we have a person assigned to sort of be a guard at the door and say, for everyone who is going to rush in, are they properly dressed? I have to completely change out from my street clothes to a different set of scrubs. Then, make sure I have the correct PPE when we're in the unit. We have either a regular mask or an N95 and when we go from room to room, we have to make sure that we are wearing the equipment correctly and taking them off correctly. You have a few minutes to go in, go over everything with the patient and then everything else is done outside.

SHAH: We have to think what tests we're going to order because we're going to put someone else's life in possible jeopardy. We have to think, is that going to be so helpful that we will risk taking the patient down to a different department where we're exposing different health-care providers? That's what is totally different from what we're used to. And the hospitals are now very dramatically different. We cannot just willy nilly use any ICU. We have to use very specific ICUs and use very specific units.

MADOR: In other places where the virus has been further along in the pandemic, Italy, New York City, for example, we have heard heartbreaking stories about a lack of ventilator space, ICU beds, et cetera. How much of a concern do you have about the idea of running out of ICU beds or not having enough staff because staff gets sick, or PPE and not having enough N95 masks and things like that to go around, if we do see the worst-case scenario in terms of the surge in Ohio?

SHAH: One thing I have to give credit to Gov. Mike DeWine and [Ohio Department of Health Director] Dr. Amy Acton that we as a state really took measures early in this pandemic and those actions are paying off. I would say 10 days ago we were possibly projecting deficits and lack of equipment but just with our careful planning, deciding how we allocate these resources, and now with our ability to sterilize the N95 masks, we are cautiously optimistic, I would say. But, you know, it's not a panacea. Everyone walking into the hospital cannot get a mask, but the people that need it, they can get it.

MADOR: This is such a crazy time. I've heard stories about nurses and doctors not even sleeping at home because they are afraid of infecting their family members. It's so difficult. And I just wonder, how are people in health care coping right now?

SHAH: This is unquestionably a very stressful time. Each one of us who work on the front line, when we go home we constantly think, I for one shower after I leave all my used equipment there, I have a totally new set of clothes once I come home. Once again, I jettison those clothes, I shower again, constantly wash hands and use hand sanitizer, try to maintain distances. But in reality, it's hard for some of our personnel who have families. I have a special-needs daughter and my wife's mother lives with us and she has dementia. So, as much as we would like, we cannot always maintain distances. I have to brush her teeth, take her to the bathroom. We do have a caregiver, fortunately, that comes some days but other days I have to give her a bath. We have to feed her. So I'm always worried that I'll pass it on to them. There are nurses that go home to 2-year-old kids, those 2-year-old kids, as much as you want to distance them, they're going to cling to their mom or dad. That weighs heavily on us. And we've all had times that we've had a little cough, could be allergies, but this time, I mean, is it COVID-19? Our muscles ache because we're tired, is it COVID-19? We've all heard of health-care providers in other parts who've gotten sick, who've gotten COVID-19. And we do the best we can.

MADOR: There is a big question in the air right now about what happens if the social distancing rules, the essential business order, stay at home order are lifted prematurely and then we see this resurgence in cases. Is that a concern for you?

SHAH: That is definitely a big concern. All these models depend heavily on maintaining the social distancing for as long as we are required to. So if people prematurely celebrate victories, then we could pay a price. But if we follow those, for the most part, we should be OK.

SHAH: I just want to tell the community that, please keep doing what you're doing and follow the guidelines and instructions from the right authorities. Don't panic. Don't freak out. There is going to be toilet paper. There is going to be hand sanitizer. There is going to be milk. Be gracious to your neighbors. And if anything happens, we are here. We will take care of you. You do not have to worry about that. And hopefully we'll learn the lessons that this teaches us.

Read more about the state of Ohio's projections for the coronavirus outbreak.