Just about every big player in Ohio politics got behind Issue 1 this year. It united liberals with conservatives, labor with the Chamber of Commerce, and Ohio Right to Life with NARAL Pro-Choice Ohio. Plus, it won more than 70 percent of the vote. The plan was to change how state legislative districts are drawn. Those district boundaries are seen as playing a major role in determining which party controls lawmaking at the Statehouse. But Issue 1 did nothing to change who draws Congressional districts.

Now, some in that coalition who backed Issue 1 say they have the wind at their back in the next effort—changing how Congressional lines are drawn.

But after the election, Ohio’s Republican state house speaker, Cliff Rosenberger, said not so fast.

“We gotta let this process work its way through. We just passed Issue 1 on the ballot. Now let’s give it a test. Let’s see how the whole thing works itself out.”

“He literally was talking about, hey, we need to wait another 17 years before we tackle Congressional redistricting reform," said Catherine Turcer with Common Cause Ohio. Districts are redrawn after the Census each decade, and she says the state would have to wait a long time if it missed its opportunity at reform before 2020.

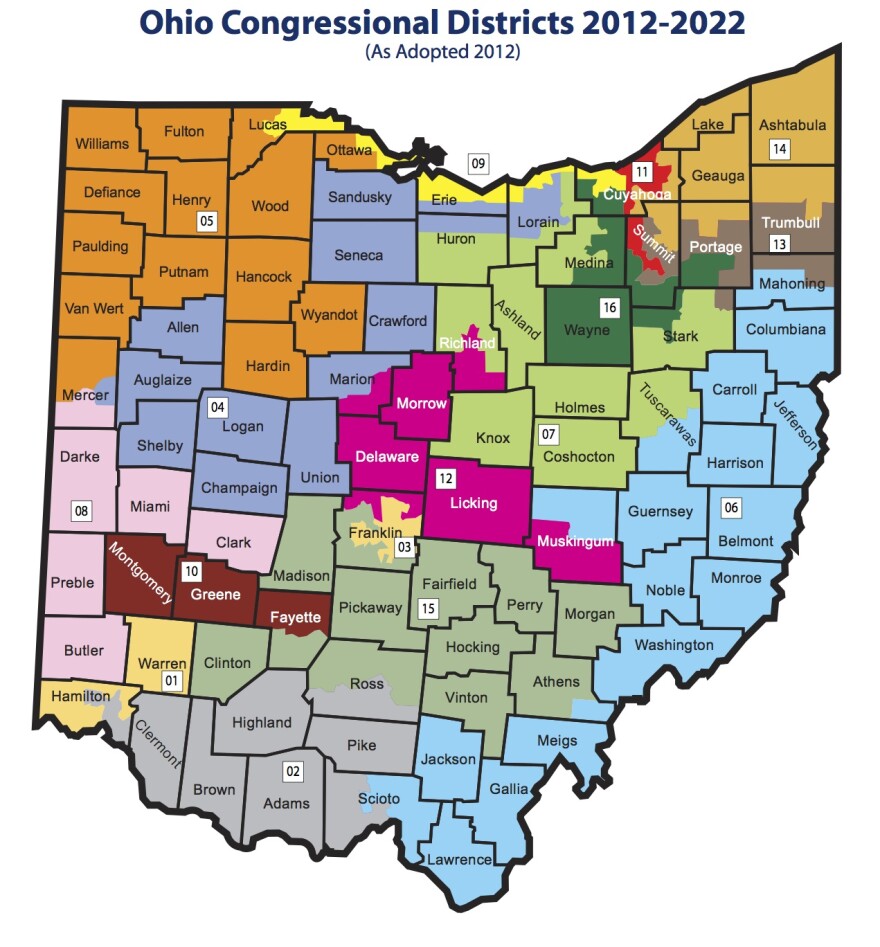

The last redrawing of the districts melded two seats held by Democrats into a 100-mile long district that winds along the Lake Erie coast. Toledo-area Congresswoman Marcy Kaptur found herself in a primary fight.

"They took a pencil and they drew it right around my backyard, and they went all the way to Cleveland, and they drew it behind Dennis Kucinich’s backyard, and they decided it would be a great idea if we ran against one another.”

There are proposals now in the state House and Senate aimed at Congressional redistricting.

Republican State Senator Frank LaRose and Democratic Senator Tom Sawyer want Congressional districts drawn by a commission made up of the governor, other statewide officials and appointees of lawmakers from both parties.

That would give more power to the minority party in a process now controlled by the GOP. LaRose says he’s okay with that, “I want to be a member of a party that wins elections based on our ideas, based on our solutions and the way that we govern, and wins competitive elections because we have better candidates. I don’t want to be a member of a party that rigs the system in order to win.”

LaRose says his plan has run into some resistance, though, from members of his own party.

“The shoe could easily be on the other foot, though, and that’s what I often try to remind people. Nothing’s permanent, and as much as you like the process right now because your party’s in control, you will loathe the process equally when your party’s not in control.”

Both parties—as well as good-government groups—had tried for years to change the redistricting process in Ohio. Until this year, all failed.

In 2012, a proposed constitutional amendment would have created a 12-member citizen commission to draw both statehouse and Congressional district lines. It didn’t have bipartisan support and more than 60 percent of voters rejected the idea.

Former Republican State Representative Matt Huffman helped lead the campaign for the successful Issue 1 and says it took months to negotiate a deal.

“Congressional redistricting is not going to happen unless both sides come together and come up with a plan that they both agree on. And the fact that a Republican and a Democrat introduce something doesn’t mean that.”

Ohio has some role models in other states that have had success passing redistricting reform.

In 2000, a voter-led petition in Arizona put redistricting in the hands of an independent body. A few years ago, the legislature sued, but the U.S. Supreme Court this summer ruled against them.

In 2008, California voters created the Citizens Redistricting Commission to draw state legislative boundaries. Two years later, 61 percent of voters gave the commission power to draw Congressional lines too.

Michael Li is an attorney with the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University. He says Ohio’s successful Issue 1 amendment will give a boost to other similar efforts in states like Illinois and South Dakota.

“So really this does seem in a lot of ways to be a reform moment, and this is drawn from a growing sense that redistricting is an important part of the dysfunction in our government, both at the state level and at the federal level.”

The latest plan in Ohio is still in committee, but advocates hope their victory in the last election provide momentum for another win in the coming years.