Montague took WYSO hunting for microplastics on the edge of the Great Miami River, next to the I-75 overpass in Dayton, as birds and big rigs flew overhead.

“Here’s just a teeny piece of plastic,” he said. “Definitely a microplastic. Just that little blue dot, that's a piece of plastic.”

It’s easy hunting. Ben held out his hand. On the tip of his index finger, there was a small speck of bright blue. He put that in a bag, then reached for another speck. This time, it was yellow.

“So, at one point, this was a much bigger piece of plastic. And it just keeps breaking down and breaking down to the point where you won't even be able to see it. And that's where it becomes dust in the air. And we breathe this stuff in all the time because it's so small that it's floating in the air,” Montague said.

He says microplastics can be ingested in other ways too, like eating and drinking.

“When I first started researching it, the big thing was that they had found microplastics in a beer. And now, it's in placentas, and it's in people's bloodstreams. I mean, it's everywhere now.”

Researchers have found microplastics in people’s lungs and bloodstreams and placentas. And microplastics are in pretty much every body of water. Montague has collected them from the Caribbean Sea and from lakes in New England. He says he found a beach in Spain that was as much plastic as sand.

“It was incredible,” Montague said. “It was a beautiful tourist town, and people are just walking along in the sand, not realizing that there’s so much plastic in that sand, that that’s essentially what you’re walking on.”

In short, it’s everywhere in every way, and he wants to raise awareness.

But Montague is quick to note he’s an artist, not a scientist. So, we’ll travel upstream about a mile, to the University of Dayton, to talk with Dr. Justin Biffinger about why microplastics are so ubiquitous and sort of invincible.

“The bottom line is that microplastics are really difficult to degrade because they're so hard,” Biffinger said. “They're also the most chemically inert pieces of the plastic. And as a result biology and life really hasn't found a way to degrade them.”

Biffinger knows about this stuff. He’s leading a multimillion dollar research project that partners the University of Dayton with the U.S. Air Force Lab at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, the U.S. Naval Research Lab in Washington, D.C. and Central State University.

They’re studying fungus — a fungus that has the Department of Defense concerned. That’s because it eats at the polyester polyurethane coatings that protect weapon systems inside of warplanes.

Biffinger’s team found this fungus does degrade parts of the coating, which could help in eliminating microplastics in the future, but it doesn’t degrade everything.

“The components that it can degrade, it will. The components that it can’t degrade, it won’t, and that then ends up releasing microplastics, probably indiscriminately,” he said. “So, we can think about microplastics that way. Microorganisms don’t want to deal with them either.”

Biffinger says there’s no clear way to significantly reduce the amount of existing microplastics in the environment right now.

“I know it's an awful answer, but microplastics are an eventuality. They are naturally coming off of every polymeric material that we have. But it is certainly on the radar of several different funding agencies that are trying to focus on sequestering them and trying to understand ways to condense them and concentrate them in order to then get rid of them.”

With no current solution to the great volume of microplastics humans produce, the problem isn’t going anywhere soon.

That brings us back to Benjamin Montague’s attempt to raise awareness.

Paula Wilmot Kraus unwrapped and installed Montague’s exhibit at the Rosewood Arts Center in Kettering.

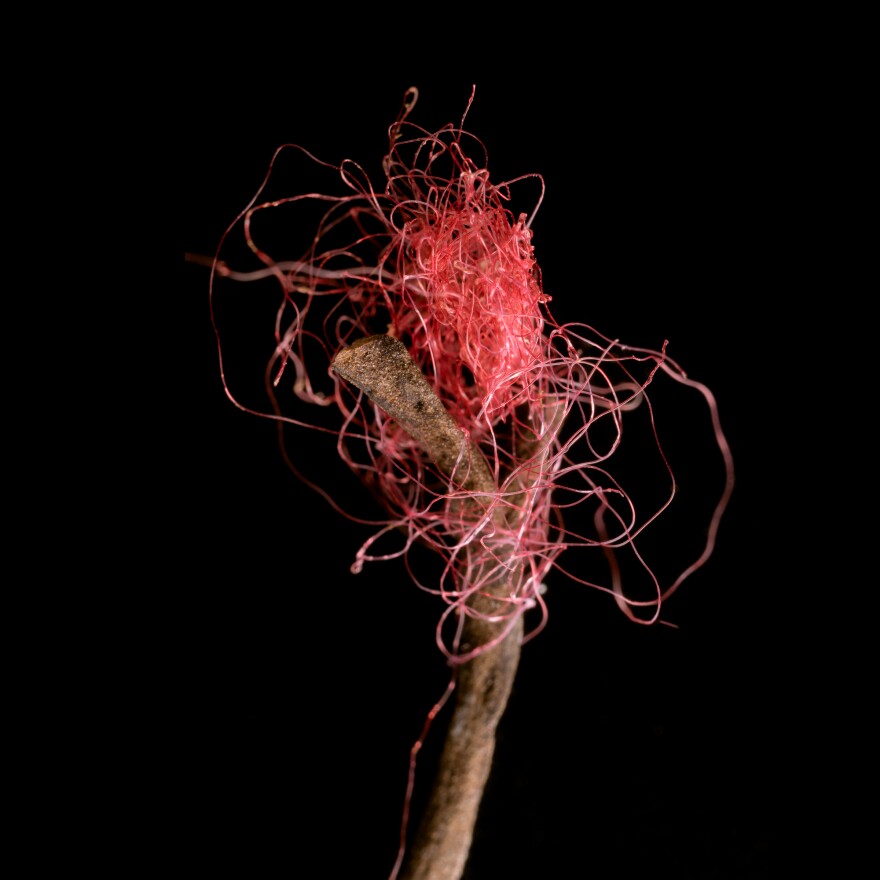

“This is the fun part,” she said, ripping open a package. “It’s like Christmas opening these packages.” And she held up a large framed photo that captures a swirl of different brightly colored microplastics. There are supersaturated reds, blues, and greens.

The colors are so rich, they look harmless, inviting even. These are the plastic colors of kids toys and soda pop bottles.

“You know, it looks like a beautiful thing,” Kraus said, “but oh… It’s just nasty that this is in our waterways.”

While microplastics are under 5 millimeters, Ben’s prints are all over a square foot. Many are much larger.

Some of the prints zoom in on and enlarge single pieces of microplastic, as well as the things surrounding them. In one large print a mayfly nymph — a baby insect that’s only a few millimeters in length — examines a pale blue, plastic cylinder in the water. It’s a microplastic even smaller than the nymph.

Kraus says this is why art is important.

“People need the story told in many ways,” she said. “If they don’t hear it from a scientist, if they don’t hear it from a newscaster, maybe an artist will get the point across.”

Benjamin Montague’s exhibit is on display now at the Rosewood Arts Center, and he’ll be giving an artist’s talk at the Center on August 26.

Copyright 2023 WYSO