Just about every place has a local hero, a hometown kid who grew up to make their mark on the world. In Yellow Springs, Ohio, one hometown hero made her mark on the world of children’s literature.

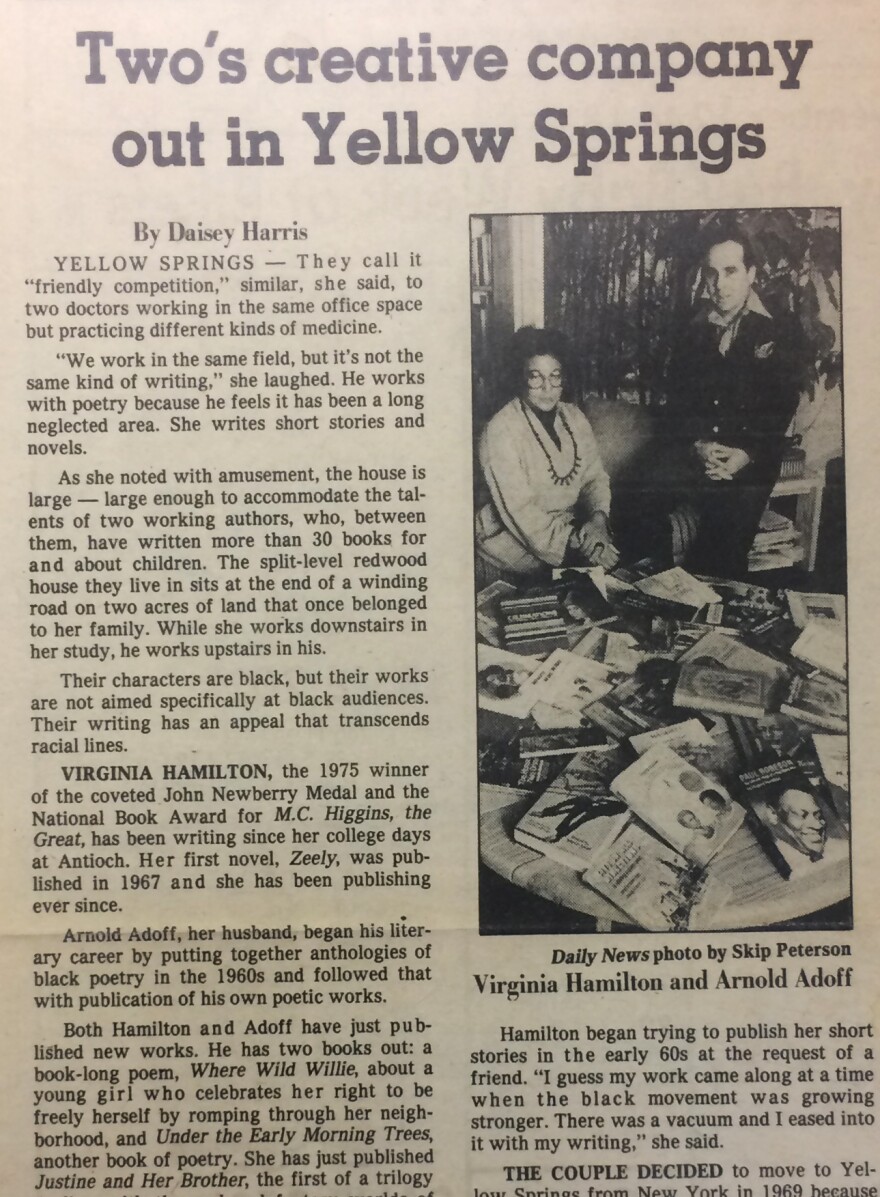

Although she passed away in 2002, Virginia Hamilton’s legacy continues through her large and varied body of work written for young people. It’s also been kept alive by her husband Arnold Adoff, by her children Leigh and Jaime, and by the recent publication of a biography for young readers.

In the WYSO Archives, we have two recordings we’re sharing in this very special edition of Rediscovered Radio. One is from 1981. It’s of former WYSO news director Willa Seidenberg's interview with Virginia Hamilton, and it features dramatic readings of her work. It also reveals the inspiration her home town provided for her writing.

The other digitized tape is an interview with Virginia Hamilton’s husband, poet and anthologist Arnold Adoff. It was recorded in 1983, and in it he speaks his poems as only he can do.

These recordings give us a glimpse into the lives of two people who quietly made their home in a little village in the Midwest and raised their kids, all the while creating great change in the literary world.

Beginning with the publication of her first novel, Zeely, in 1967, Virginia Hamilton wrote from an African American perspective, from what she called the experience of a “parallel culture.” She refused to use the term “minority” because she felt it minimized the experiences of non-white people. But she also told stories of the universal experiences of childhood and young adulthood, in ways that transcended race.

Arnold, too, was breaking new ground in literature. His poetry anthology, I Am the Darker Brother, was published in 1968. It was one of the first compilations of Black poets’ work created especially for young people.

Together, they blazed a path through the publishing industry that opened the way for others to follow.

When WYSO’s Willa Seidenberg talked with her 35 years ago, Virginia Hamilton had already been recognized with the most prestigious award in children’s literature; she had won the John Newbery Medal in 1975 for M.C. Higgins, the Great, a coming of age story set in the Appalachian Mountains. And she was the first Black woman to receive the award. By the time of this interview, she’d also been recognized with the Edgar Allen Poe Award, the Boston Globe-Horn Book Award, the Coretta Scott King Award, and the National Book Award, making her one of the most honored authors in children’s literature. Many more awards would follow, including the Hans Christian Andersen Medal in 1992, and a MacArthur Fellowship in ‘95.

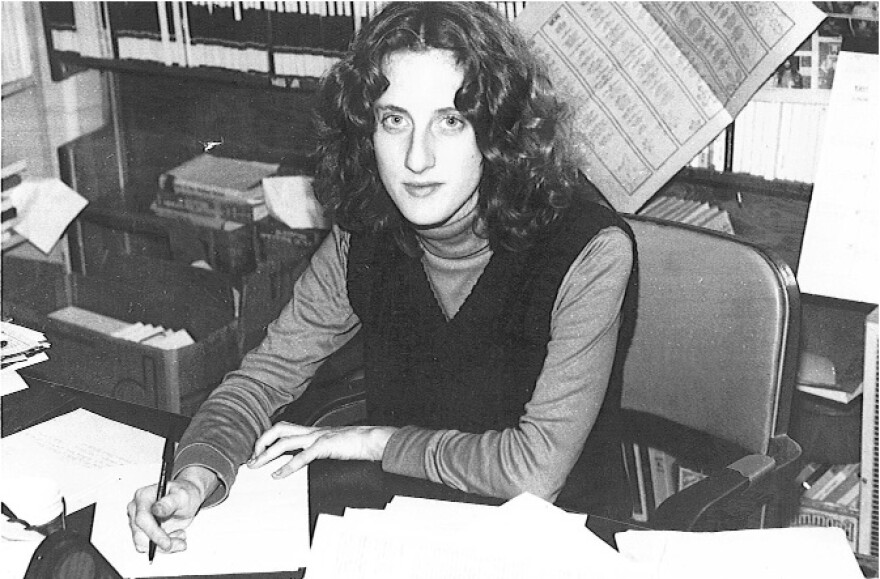

But in the archival audio, Seidenberg, who today is professor of professional practice in the Annenberg School of Communications and Journalism at the University of Southern California, learned of Virginia Hamilton’s journey to becoming a children’s author. It wasn’t what Virginia set out to do, at least not at first.

"I majored in writing here at Antioch," said Hamilton in 1981. "And I was simply writing stories and for many years tried to get published, I had an agent, and I had a long correspondence with The New Yorker about stories. I always wanted to be a New Yorker writer but I couldn’t quite fit into that mold, but they were very nice and very encouraging. And I was writing adult stories and I had a friend who went to Antioch who was working for Macmillan and happened to be working in the children’s book department. She remembered my stories from Antioch and said they would make good children’s books and I said what’s a children’s book because I didn’t know. So, one of those stories, which was called 'The West Field' became my first book Zeely and I had no problem getting published once I started writing children’s books."

Virginia spoke, too, of the impact of her African American identity on writing and storytelling.

"I don’t think you can, if you’re a Black writer writing about Black subject matter, you can stop from being symbolic. It just simply happens, you know, and anything, any problems that I might have in this society comes through my literature, I don’t even have to try, it’s part of the stories that I tell, you know, I believe that. I don’t go about trying to put messages in, they’re just there."

Virginia Hamilton was a highly successful author; she wrote 41 books, from folk tales to fantasies, mysteries to biographies. She traveled widely, speaking at literary conferences and award ceremonies all over the world. But that wasn’t always the case.

"Writers frequently say that the most difficult thing in the beginning is getting published, trying to get somebody who will publish you," Willa Seidenberg said in her interview with Hamilton. "Did you find that I mean that that’s a strike against you just to start out with it you have try and…"

"Right, it is extremely difficult and it is probably the worst system I’ve ever encountered in any kind of business, you know, you would think you would make it easy for people to get in it, but it’s not, it’s very difficult. It’s still the kind of business that if you know somebody it’s a lot easier. Now I couldn’t get an agent for about five years, and I couldn’t get an agent because I wasn’t published. You know, and it just went around and around. I couldn’t get published because I didn’t have an agent. But it’s just extremely difficult and we help a lot of people, people in this town who have gotten published, because we knew where to get the stuff in. You still have to have the goods, but sometimes you have it and you can’t find the right publisher or you don’t know where to go.

"So, as a writer who has been successful in getting published and has become a successful writer, you feel a responsibility to help other writers who are coming along?" Seidenberg asked.

"Oh yes," Hamilton replied.

The interview also touched on Virginia’s creative process, and her unique genius in bringing forth her stories.

"I’d like to just ask you about your process of writing, what is your process from the beginning of the germ of the idea for the story to..." Seidenberg began.

"That’s what I was doing in Chicago yesterday," said Hamilton. "Telling everybody about the creative process, and you end up saying I don’t know how I do it! All I can say is that suddenly I have an idea, and I don’t know where it comes, or I have a picture or I have an image, you know, and I begin to play around with it. Usually it’s an idea. My editor who is the editor in chief at William Morrow Greenwillow Books says that it’s not true, that this is a story that I’ve made up, I really start with character and she says whether I’m aware of it or not I have a character in my first, and I’ve denied it for ten years, but she’s probably right, I’m slowly coming around, trying to slow down, this is a lightning swift process, it’s something that you don’t really think about that is happening, it just starts happening. And I think she’s absolutely right, I start with a character and characters define plot and action, they define the book It’s what your characters do that make a story, it’s not the story first and then your characters."

"I think that it’s, I mean I always feel funny when I ask any kind of artist, writer, or artist about their creative process because I think it’s hard for people who aren’t, who don’t have that creativity to understand, I mean, I just keeping thinking when I talk to people, how do you do it?" asked Seidenberg.

"That’s right," replied Hamilton. "And it’s very difficult. My theory is that if you have an idea, someplace you also have the mechanism for creating a whole system for that idea. And so far it’s been so, you know. But the creative process is extremely elusive, and I don’t know how you can ever explain it although that’s what I do all the time, I go around the country trying to people say, where do you get your ideas and how do you do it and those are the hardest questions because I can’t tell them you know, really, I can only do it I suppose if I could tell them I couldn’t do it, you know."

These decades old interviews permit us to gauge how far we’ve come, and how far we have yet to go. In the late 1960s, the number of authors writing books for children of color were few, so few books existed in which Black and brown children could see themselves represented. Together, Virginia Hamilton and Arnold Adoff worked to change that.

Back in 1983, Marcie Sillman, now an arts and culture reporter for KUOW in Seattle, was a producer at WYSO, when she interviewed Arnold Adoff, then a robust 48 years old. From singing his poems to critiquing the publishing world, Arnold was a lively interview subject.

"Well, Virginia and I were fortunate," he said. "We had the horses, we had worked hard, she went to Antioch, she went to Ohio State, I went to City College and Columbia, we spent many years in New York writing and studying and working with people. I worked with a superb Filipino-American poet named Jose Garcia Villa who was a protégé of Sitwell’s, and we all have our influences, but by the 1960s and during the Civil Right Movement when things began to open up in America for non-mainstream groups, because of agitation and activity, Blacks becoming more visible, people talking about the white problem rather than the Black problem, we were there, and we were ready, and I had my anthologies, Virginia her novels, and the publishing industry was rolling and expanding.

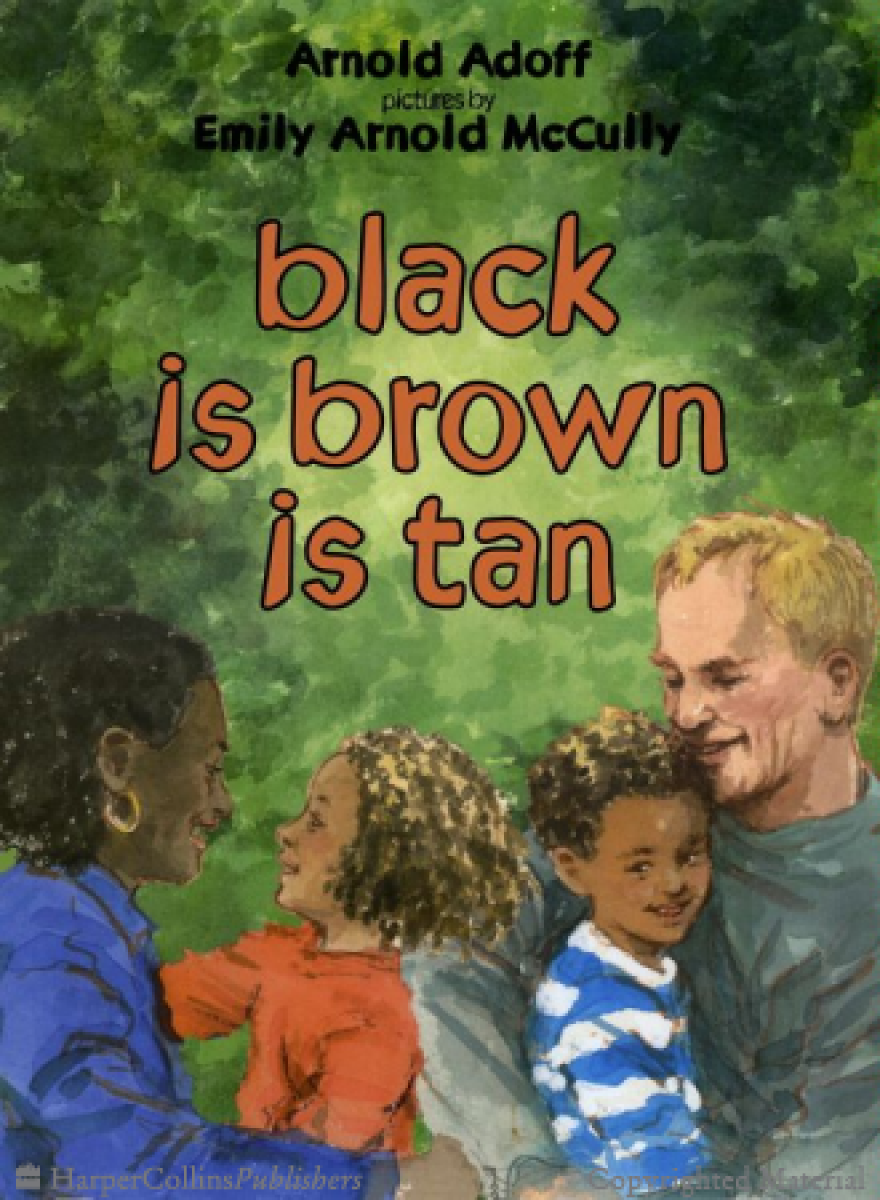

Because of my interracial marriage and my children who are Black and white, I’m interested in that duality, in that combination of cultures, and beyond just Black and white to all cultures in a pluralistic, humanistic society, and so two of my most important books are called Black Is Brown Is Tan and All the Colors of the Race, which deals specifically with what it is to be an interracial young person in the world.

So, a book like Black Is Brown Is Tan, which was the first book poetry or prose really to deal with an interracial family in literature for children, is used by the vast and various combinations of peoples that we have in America, which is exciting and wonderful and sad as well, because there should be one with a Black father and a white mother, and one with Chinese and Korean and Vietnamese and Cambodian and Southern Appalachian and North West American Indian mixtures that we find any and everywhere around America. Of course, it’s enabled me to encounter many of these people as they come up to see me when we meet and talk. But I would hope that the adults in the audience and the adults who work with the children and the children would take some of our books and say, I can do it different, I can do it better and use them as foundation stones and go on and do their own writing from their own experiences."

Today, Arnold Adoff at 82 is no less engaged in artistic and social activism. And he still writes poetry, with a new book just headed to the publisher. When I spoke with him in the summer of 2017, he told stories of growing up in the Bronx, of hanging out in Greenwich Village with jazz bassist Charles Mingus, and of meeting and falling for a country girl from Ohio.

"That’s all she wrote," says Adoff. "It was beyond love at first sight. It was cosmic and spiritual and everything that I didn’t even know existed at the time. Two days later I went to have dinner with my mother up in the Bronx on the way to the National Guard armory where I was a member of the guard and she said what’s new and I said I met this woman, she’s Black, and I’m going to marry her, and that was the end of the conversation as far as I was concerned. As far as they were concerned, it was another cause for bringing in psychiatrists, etc., etc. etc."

Arnold Adoff continues to embody the legacy he created with Virginia, and not only through his poetry.

"So I always end my emails 'The struggle continues.' And it really is a continuing struggle from when we became aware in the Fifties and Sixties to you know to now and to the young people coming in. Extraordinary number of talented, brilliant, talented African American, not even saying, you know, Asian, Hispanic, you add those in, there are dozens of extraordinary people writing for young people, and illustrating for young people, it’s the richest of times, I think, really since the Sixties spilling over into the Seventies, and for me, that’s wonderful deciding to after she died, just make my home here in Yellow Springs, but, and to stay here, but with Facebook which is lovely, I can’t do Twitter, but with Facebook, or anything else, I can barely do Facebook, but it keeps me in touch with the next generation and the next generation, and occasionally conferences that we go to. I’ll put a plug in for the Kent State Conference."

The Virginia Hamilton Conference on Multicultural Literature for Youth at Kent State University, founded in 1985, is the longest running event focusing on such literature for young people. Usually held every spring, in 2018 it will team with a literacy conference in Northeast Ohio for a mid-October date. The conference honors authors, poets, illustrators, and books for youth that celebrate the rich diversity of this country. In 2016, the Arnold Adoff Prize in Poetry was added to the slate of awards bestowed at the conference, encouraging emerging multicultural poets as well as those writing for different age groups.

But there’s also a living legacy that Virginia Hamilton and Arnold Adoff have given the world: their two children, Leigh and Jaime.

Operatic soprano Leigh Adoff, known professionally as Leigh Hamilton, has lived in West Germany for the past 18 years, performing widely in Europe and the United States, and now, she’s teaching young singers.

Speaking from her home in Berlin, Leigh offers her memories of the parents who encouraged her life as an artist.

"Collectively and individually, they broke unbelievable barriers in children’s literature," she says. "Also, in poetry, you know my father, he was one of the first, if not the first, I don’t know if that’s 100% sure, but if he wasn’t the first he was one of the first who was anthologizing people of color’s poetry, starting in the Sixties. Poets of color, you know, and Black, Hispanic, Native American, Asian, it just, it didn’t exist.

And my mother, as a children’s book author winning every award you can win and getting these big, later, this wasn’t in the beginning, but let’s say later, this would’ve been in the Eighties, definitely, getting these big multi book contract from Scholastic and good money, that didn’t exist, and it certainly didn’t exist for a Black woman, you know what I’m saying? I mean, it was just…she was a pioneer in this arena.

And my father fought for her. He was always her agent and negotiated, she got to be the artist and didn’t have to get her hands dirty, and he was back there making the sausages, if you know what I mean. He fought for her, he negotiated those contracts, he fought them tooth and nail for every cent that she got, and he never took as an answer. Now, people said all kinds of things about him, I don’t care, because whatever Virginia Hamilton wanted he made sure she got it, and that isn’t just love, but it’s an unbelievable amount of respect for this person’s incredible talent and hard work, you know. I mean I just think that they broke barriers as a biracial couple, let’s say, you know when they got married there were still something like twenty some odd states where that would be illegal.

And then on a professional level, the things that they did had not been done before. And now you know, there’s still not enough people of color’s work being represented and published, but it is infinitely better than it was thirty years ago, 35, 40 years ago, you know. And I think for me, that’s one of the things that makes me most proud. Of course, all the awards and recognition are wonderful, but that they really helped to pave a way for people, for artists, for writers now, and that these things are possible and not out of reach because they did it."

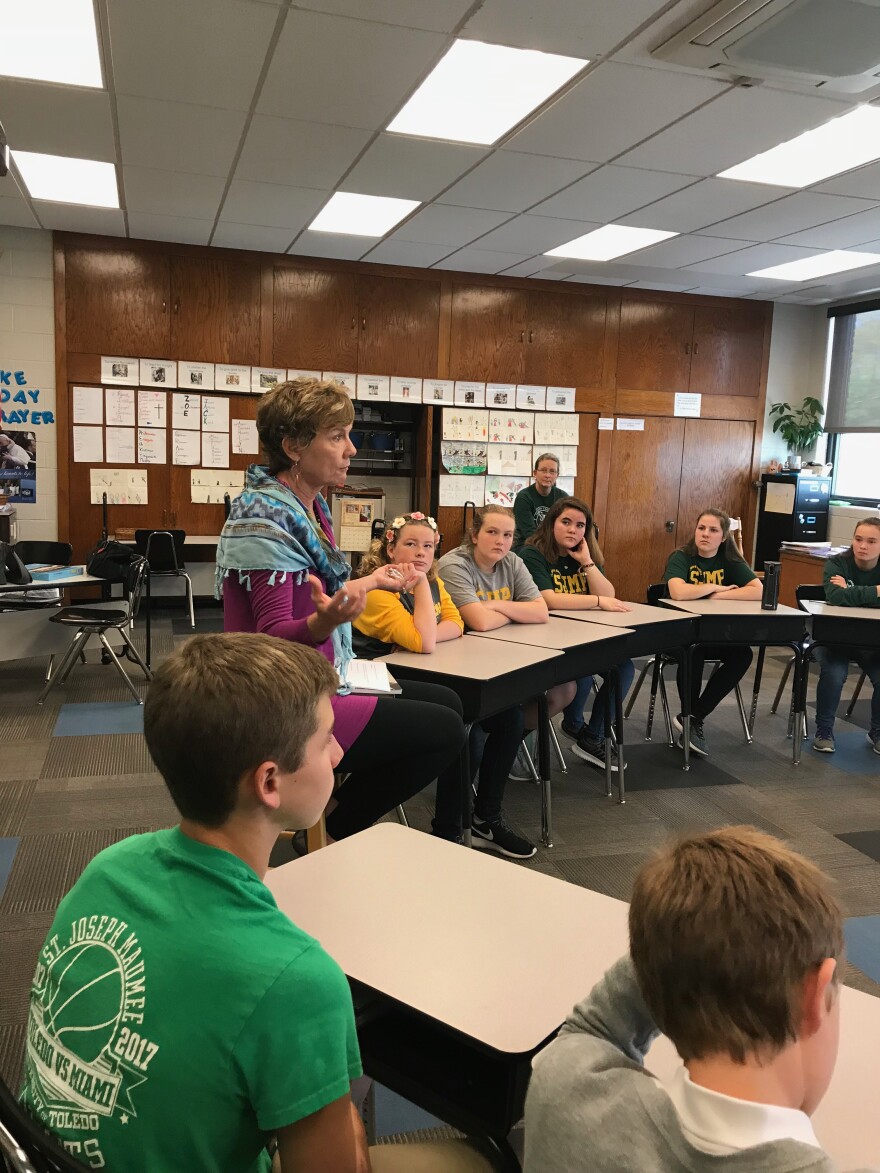

Brother Jaime is also a trained musician, as well as an award-winning writer. But Jaime found his true calling as a middle school teacher. Growing up as the son of two famous writers, he saw the creative process firsthand.

"I learned mainly by example," he says. "Watching my mother every morning going into her study, locking, not physically locking herself in, but going in with a cup of coffee, and I’ve told this observation for years, when I was a little kid she would walk in with a cup of coffee, and then you know, four or five hours later, six hours later, it would seem she would have pages and pages of writing, so as a small child I thought if you poured coffee on paper, you got creative writing. So, no I saw the creative process up close, it was a part of me before I even could probably you know really realize or talk about it, and then seeing my dad work on poetry upstairs, they worked full time at home so there was a lot of access to them."

Jaime has been recognized as a finalist for the Teaching Tolerance Award for Excellence in Teaching sponsored by the Southern Poverty Law Review.

"There was a point where I was traveling as a travelling author speaking around the country," he says. "Where I just realized it wasn’t enough because I would go into schools and then I would leave after a day or two, and I wouldn’t know what happened to the kids. So, then it became well, I need to be on the scene and see what can I do to have a more lasting effect."

But Arnold and the family aren’t the only ones keeping Virginia’s memory present and pertinent. Author Julie K. Rubini’s Virginia Hamilton: America’s Storyteller, published in 2017, is geared toward the young people for whom Virginia wrote.

"Her legacy is in that incredible body of work that still lives on the shelves of school and public libraries," says Rubini. "And I think Arnold’s efforts and through their children, their efforts and through my efforts in writing the biography and so many other educators and librarians who embrace Virginia’s work, the legacy will be to continue to create this awareness of both her work as well as Arnold’s works. Her legacy is so even beyond her works, it’s that legacy of trying to help other authors have their works published, it’s in the legacy of creating incredible stories for children that were unlike any works previously and unlike many works that are out there today. And her works are so varied, you could read one of her folk tales, and then read House of Dies Drear, M.C. Higgins and one of her biographies, I mean she was just, she was an amazing writer and I felt very honored to share her story."

Virginia Hamilton blazed a trail for many of the authors of color who write for young people today, like Kwame Alexander, Jason Reynolds, Jacqueline Woodson, Tony Medina. Along with Octavia E. Butler, Virginia Hamilton is also credited with inspiring speculative fiction authors like Nnedi Okorafor, and others writing fantasy stories that draw on the folk lore of the African diaspora.

"And in that particular sense, we can look at her as a type of literary foremother who really helped pave the way and opened up the literary landscape in order for more diverse voices to contribute to the speculative fiction category," says Dr. Sharon Lynette Jones, professor of English and director of African and African American Studies at Wright State University. "I think that Virginia Hamilton was truly groundbreaking. I think that the way in which her work engages with class, race, gender, and other elements really has set up a foundation for a lot of contemporary writers."

As is fitting for a great American writer, Virginia Hamilton’s papers, her correspondence and manuscripts, are archived at the Library of Congress. Also, the extensive research library collected by Virginia and Arnold over the years was donated to Wright State University’s Bolinga Black Cultural Resources Center in 2010.

Dr. Jones spoke of what it means to pass the Virginia Hamilton and Arnold Adoff Resource Center, on the way to her office, "It is profoundly, you know, and deeply moving to walk past that every day, and it inspires me, it empowers me and it helps energize me in my work as a writer and as an educator, and it shows how their legacies continue to live on."

Virginia Hamilton’s legacy does continue to live on. In the spring of 2017, Virginia was honored with a historical marker placed in front of the Yellow Springs branch of the Greene County Public Library. It reads in part:

Her books have had a profound influence on the study of race throughout American history, the achievements of African Americans, and the ramifications of racism.

And in January of 2018, she was honored yet again, by the Capitol Square Foundation at the Ohio State House in Columbus with their Great Ohioan Award. She joins other notable Buckeyes, including Paul Laurence Dunbar, John Glenn, Jesse Owens, the Wright Brothers, and Annie Oakley. Always the trailblazer, once again she is the first African American woman to be so honored.

But Virginia remains first and foremost a hometown hero, daughter of the fields and berry patches of Yellow Springs. Her story echoes from the woods on the western edge of the village, where Arnold still writes her love poems.

Special thanks to Arnold Adoff, Leigh Hamilton Adoff, and Jaime Levi Adoff for their generosity in sharing memories of their beloved wife and mother. This special broadcast was made possible by the support of the Greene County Public Library.